1. Introduction¶

An estimated 80% of human proteins cannot be drugged with current small molecule drugs.[1] Therefore, great effort is put into developing new modalities to expand the druggable biological space. New modalities include any molecule not classified as a small molecule drug.[2] While these modalities make more protein targets accessible, they often suffer from suboptimal and less understood pharmacokinetic properties than traditional small molecule drugs.[3] Cyclic peptides (CPs) are one such proposed new modality, which are shown to bind protein surfaces and mimic protein loops to imitate protein-protein interactions (PPIs).[4] These molecules are just small enough to be cell permeable in addition to being stable and long-lived enough to reach targets in high concentration.[5] Over 40 orally available CPs are on the market[6] and in phase III studies, but many CP drug candidates still struggle to control pharmacokinetic properties, especially cell permeability.[7] This is because classic rules to predict ADME properties for small molecules usually do not apply to CP.[3] The cyclic constraint, responsible for conformational preorganization, higher binding affinities, and increased proteolytic resistance, makes it challenging to predict the 3D structure with conventional conformer generators.[8] Specialised conformer generators exist nowadays[9, 10, 11], but fast prediction of dynamic properties is unsolved.[12] This is because macrocycles exist as ensembles of several low energy conformations in solution, with the bioactive one as low as 4%.[13] Predicting which of the possible conformations are biologically relevant is hard, and may also depend on the environment.[14, 15] Determining the relevant conformers in solution and their 3D structure is crucial for predictions of pharmacokinetic properties.[16]

1.1. Conformer Generators for Cyclic Peptides¶

In the last 15 years or so, specialised conformer generators were developed to reproduce x-ray crystal structures of CPs, since classic conformer generators do not perform well.[17, 18] A range of commercial and open-source methods (OMEGA[9], RDKit[11], BRIKARD[19], MacroModel[10], etc.) now exist, but it is unclear which method performs better. Computational methods tend to work well for finding solid state structures or enumerating structures for docking studies.[9, 20] However, predicting dynamics-based properties (solubility, cell permeability, etc.) remains an open challenge, as demonstrated by poor performance of solubility predictions of cyclosporine A in the recent SAMPL challenge.[21] To produce conformers with associated information about dynamics, thermodynamics, or explicit solvent interactions, we can apply conformer generators based on molecular dynamics (MD) or similar methods.[20] The downside of these methods is increased computational cost.

1.1.1. Molecular Dynamics based Conformer Generators¶

While the cyclisation of peptides is beneficial for increasing binding affinities,[22, 23] it makes predicting solution structures difficult. Macrocyclic systems adopt several distinct conformations separated by high energy barriers.[24] Achieving adequate sampling for such systems in MD simulations is challenging. The initial conditions determine which parts of the potential energy surface can be explored during a simulation. Systems can easily get stuck in one minimum of the potential energy surface (PES) in the given simulation time.[25] Fortunately, enhanced sampling MD methods were developed which allow increased sampling of the PES despite high energy barriers with comparable computational resources to conventional MD (cMD) simulations.[26] For a generally applicable conformer generator, we cannot assume prior knowledge of the system and therefore only unconstrained enhanced sampling methods without specification of reaction coordinates can be used.

Accelerated MD (aMD), and Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) are two closely related, enhanced sampling methods that do not require specification of reaction coordinates. [27, 28] They both effectively flatten the potential energy surface by adding a boosting potential to reduce energetic barriers.[29] Through this, much faster sampling compared to cMD simulations can be achieved.[27] Enhanced sampling comes with the caveat of having to reweigh the resulting trajectory to reproduce physically correct quantities.[26] Kamenik et. al. demonstrated recently that aMD is suitable to reproduce experimentally measured NOEs (Nuclear Overhauser effect) and x-ray structures of three CPs/macrocycles. An advantage of this method is that after reweighting the original thermodynamic information on the original PES is retained.[25] Alternative methods to study cyclic peptides in solution include replica-exchange MD (REMD)[30], Complementary-Coordinates MD (CoCo-MD[31]), Multicanonical (McMD[32]), among others.[20]

1.2. How can we assess the Performance of different Conformer Generators?¶

Many suitable macrocyclic x-ray crystallographic structures are available in public databases. These structures are easy to compare to since a full structural model is available. Several compiled datasets of macrocycles are available, including the Sindhikara set consisting of 208 solid state conformations of macrocycles.[10]

The most used metric for comparing conformer generators to experimental structures is the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions. In the words of Hawkins et al: “While we and others have pointed out several important deficiencies in RMSD […], it has remained stubbornly difficult to replace in the minds of most developers and users of molecular modelling software.”[9] Other available but less commonly used metrics include 3D shape comparison,[33] bounded atom-centric measures,[34] and measures of torsion deviation.[35]

Solution state structures of macrocycles are more challenging to find since many solution structures are not deposited in databases. Experimental data comes from solution NMR studies but is often underdetermined.[20] Common experimental metrics from NMR experiments are NOE distance constraints and torsion angles (derived via 3J coupling constants).[20] Computational structures are directly compared to these metrics, especially to NOEs, which represent an average value over all accessible solution conformations.[4, 25, 30] Alternatively, ensembles of possible solution structures can be generated via a NAMFIS (NMR analysis of molecular flexibility in solution) analysis from NMR data.[13, 36] This analysis deconvolutes the NMR signal into distinct conformer contributions, such that the same metrics used for the solid state comparison can be applied.[16]

In this study, we systematically compared (G)aMD simulations with different chemical informatics-based conformer generators to assess how well they reproduce solution structures. We assembled a dataset of macrocycle solution structures termed MacroConf. Further, we developed computational workflows to automatically setup, run, and analyse MD simulations. In the following section, I will introduce the research objectives for the work underlying this report, but also explain the overarching project plan for the whole DPhil. Then, I give details about Methods and Results, before concluding with a brief Discussion. Finally, I sketch potential Future Work, including a proposed schedule (Gantt Chart).

1.3. Research Objective¶

1.3.1. Outline of the General Project¶

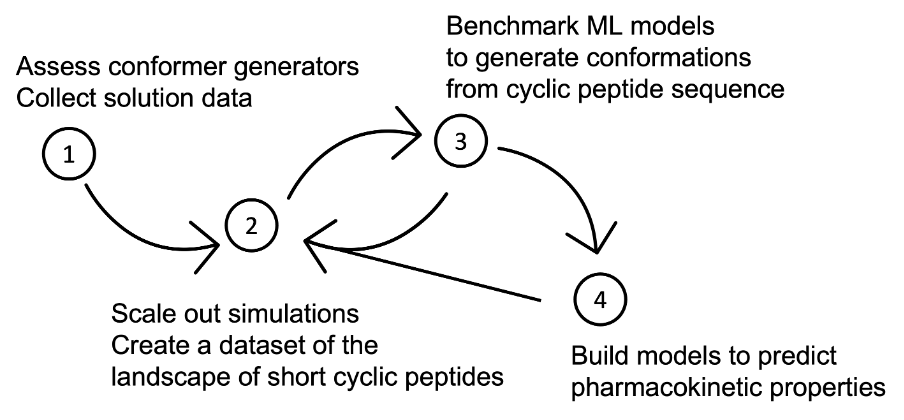

We divide the project into four steps (Fig. 1.1). The first step (covered by this report) is to gain insights and preliminary data of cyclic peptide solution structures and conformer generators. Following this, we will use suitable conformer generators to build a dataset of cyclic peptide solution structures (step 2) linking the sequence to 3D structure and pharmacokinetic properties. We will then leverage this dataset to build machine learning (ML) models to predict pharmacokinetic properties (step 4) and conformers (step 3) from sequence. Steps 2-4 are linked, and insights made in these steps will influence each other. Steps 2-4 are outlined in more detail in Section 5.

Fig. 1.1 Research plan. Step 1 is to assess different conformer generators and their ability to reproduce solution structures of cyclic peptides. In step 2, a suitable conformer generator will be used to create or augment a dataset of short cyclic peptides. The following steps will leverage this dataset to train ML models to predict conformers (3d structures), as well as pharmacokinetic properties of interest.¶

1.3.2. Step 1: Evaluating Conformer Generators to Describe Cyclic Peptides in Solution¶

The first step of this project is to evaluate how well different in silico methods (chemical informatics and MD based) describe the solution state of cyclic peptides. The most used metric to describe solution state structures of cyclic peptides are NOE constraints.[20] We consider the quality and reliability, as well as information value of this data. Next, we will collect available solution data for cyclic peptides in the literature and build an initial dataset. Outputs of step 1 are the initial dataset of CP solution structural data and associated computational workflows to automatically execute these benchmarks. Additionally, we hope to gain insights into how CPs behave in solution, an assessment of the quality of available solution state data of CPs, and insights into the performance of different macrocycle conformer generators. Of particular interest are the comparison of more computationally expensive methods (based on MD) that simulate dynamics of the systems to the computationally cheaper chemical informatics-based methods. Finally, we will identify a suitable simulation method to create datasets of cyclic peptide structures for the steps 2-4.